Community Based Participatory Research

August 10, 2023

Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is an important model to address health inequities experienced by communities.

Learn more about this model’s processes, interacting principles, and how funding influences the use of CBPR.

Developed by Rebecca Moriarty, VtPHI Intern

Hover above the slides and use the arrow to naviagte through the slides.

What’s Here

Defining and Understanding CBPR

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is an approach to research that, as defined by the National Institute of Health, “supports collaborative interventions that involve scientific researchers and community members to address diseases and conditions disproportionately affecting health disparity populations”(“Community-Based”). In other words, by joining forces between scientists and community members, CBPR aims to design interventions that tackle diseases and conditions disproportionately impacting specific populations who face health inequalities. CBPR highlights the importance of establishing a collaborative and equitable relationship between the community and scientists throughout the project, aiming to ensure that interventions effectively address the community’s specific needs (“Community-Based”).

With three main goals, the objective of CBPR is to foster research that integrates community engagement and adopts a comprehensive approach across multiple disciplines. This approach is geared towards creating interventions that effectively target socially disadvantaged population groups.

The three main goals of CBPR are:

Goal 1

Encourage equitable community involvement in research in order to to help enhance community capacity.

Goal 2

Establish sustainable interventions in order to improve health behaviors and health outcomes in health disparity populations.

Goal 3

Design interventions that are culturally tailored in order to expedite the transfer of research findings to communities experiencing health disparities.

Community capacity = The ability of a community to identify, mobilize, and address health issues and challenges effectively. It is the collective capability of community members, organizations, and institutions to work together and take action to improve the health and well-being of the population (Chaskin, Robert).

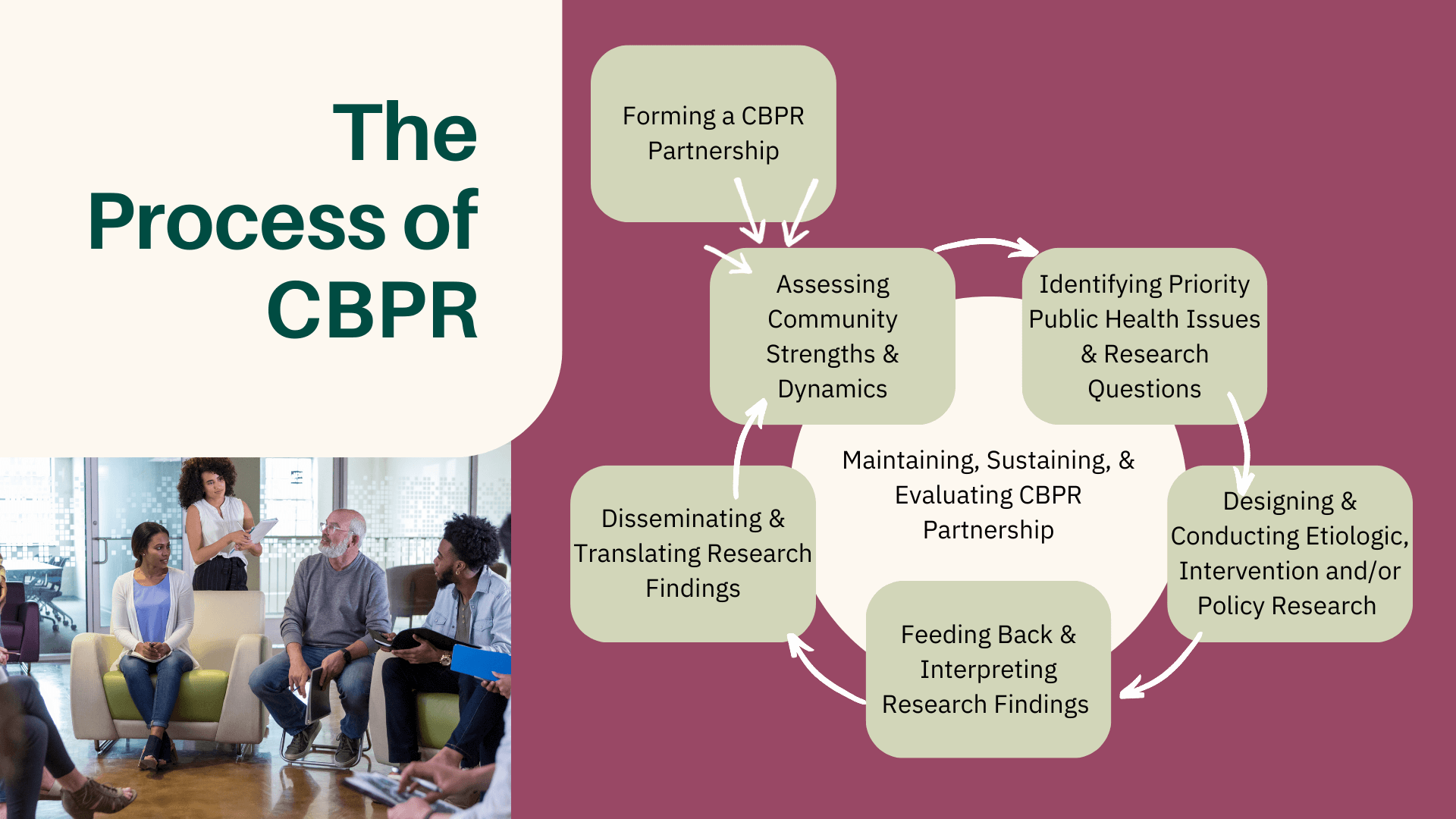

The Process of CBPR

While taking on this research approach, CBPR follows a fluid feedback loop model that involves seven core phases.

Forming a CBPR Partnership

The process starts with forming a CBPR partnership. This is an equal partnership between the community, scientists, and organizational members. This process is essential in order to promote collaboration between community members and researchers, and encourage active-participation of community members in data collection and decision-making processes.

Assessing Community Strengths and Dynamics

One of the phases is assessment of community strengths and dynamics (“What Is CBPR?”). Examples of community strengths may be accessible public transportation, material health programs, or healthy food options for kids at school. These dynamics and strengths can serve as valuable insights for the CBPR team, highlighting the community’s areas that require further analysis as priority public health issues. Additionally, they inform the identification of community programs or aspects that can be harnessed to support the CBPR research project effectively.

Identifying Priority Public Health Issues and Research Questions

The next CBPR phase is identifying a priority public health issues and research questions. These will be the issues and questions addressed in the CBPR project. In the Wapanohki Tribal Health Assessment, for example, a project conducted in collaboration between the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and the Tribal Health Departments of Maine, the identified public health issue was “the relatively small proportion of AI/AN who participate in state-wide surveys such as the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) [that] often prevents the analysis of data at the level of individual tribes that will yield meaningful results” (Johansson, Patrik, et al). The CBPR project ended with 1,127 Tribal members successfully completing the survey.

Designing and Conducting Etiologic, Intervention, and/or Policy Research

After identifying the public health issue follows the designing and conducting research phase. The CBPR project may range from etiologic, intervention and/or policy research, depending on the public health issue or research question of focus.

Learn more about etiologic research here.

Learn more about public health intervention research here.

Learn more about policy research here.

Feeding Back & Interpreting Research Findings

The CBPR project must next undergo a feedback phase and produce interpretations of the research findings. This step may involve creating graphs, charts or diagrams to illustrate and interpret the research findings.

Disseminating and Translating Research Findings

Finally, the research findings are disseminated and translated (“What Is CBPR?”). Disseminating the information collected from CBPR research is important as it enables other organizational groups to integrate this data into their own research initiatives and informs the development of interventions, such as policies and community programs, aimed at effectively addressing the specific public health issue of focus.

Given that the CBPR process operates as a continuous feedback loop, it cycles back to the assessment of community strengths and dynamics phase, followed by the subsequent phases, until the research question or public health issue of focus is effectively addressed. During this whole process, maintaining, sustaining, and evaluating the CBPR partnership is continuous throughout each phase (“What Is CBPR?”). By continuously checking in to the process, the CBPR team can ensure that the project stays on the right track and adjusts to the needs of the community as needed.

Principles that Interact with CBPR

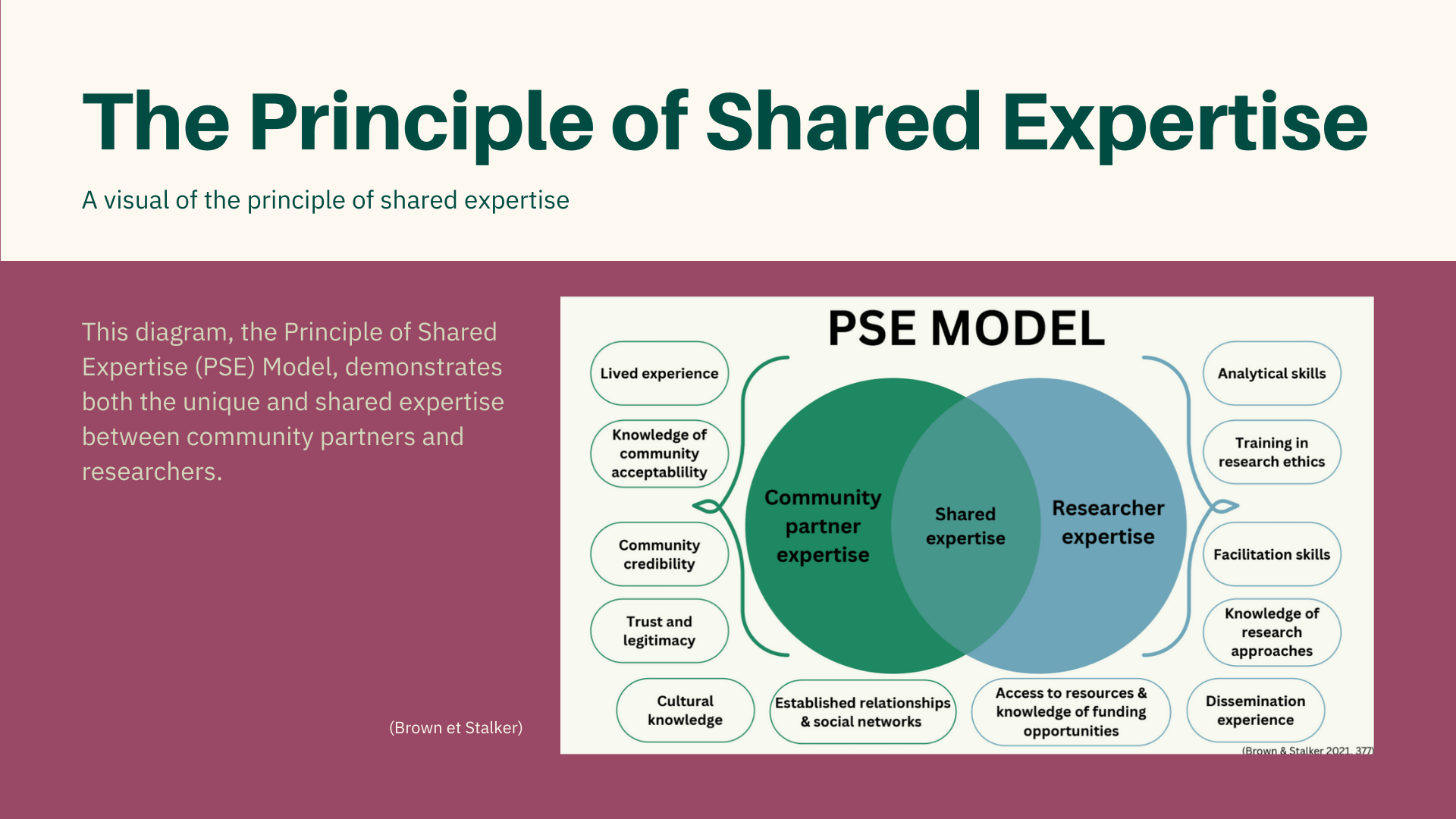

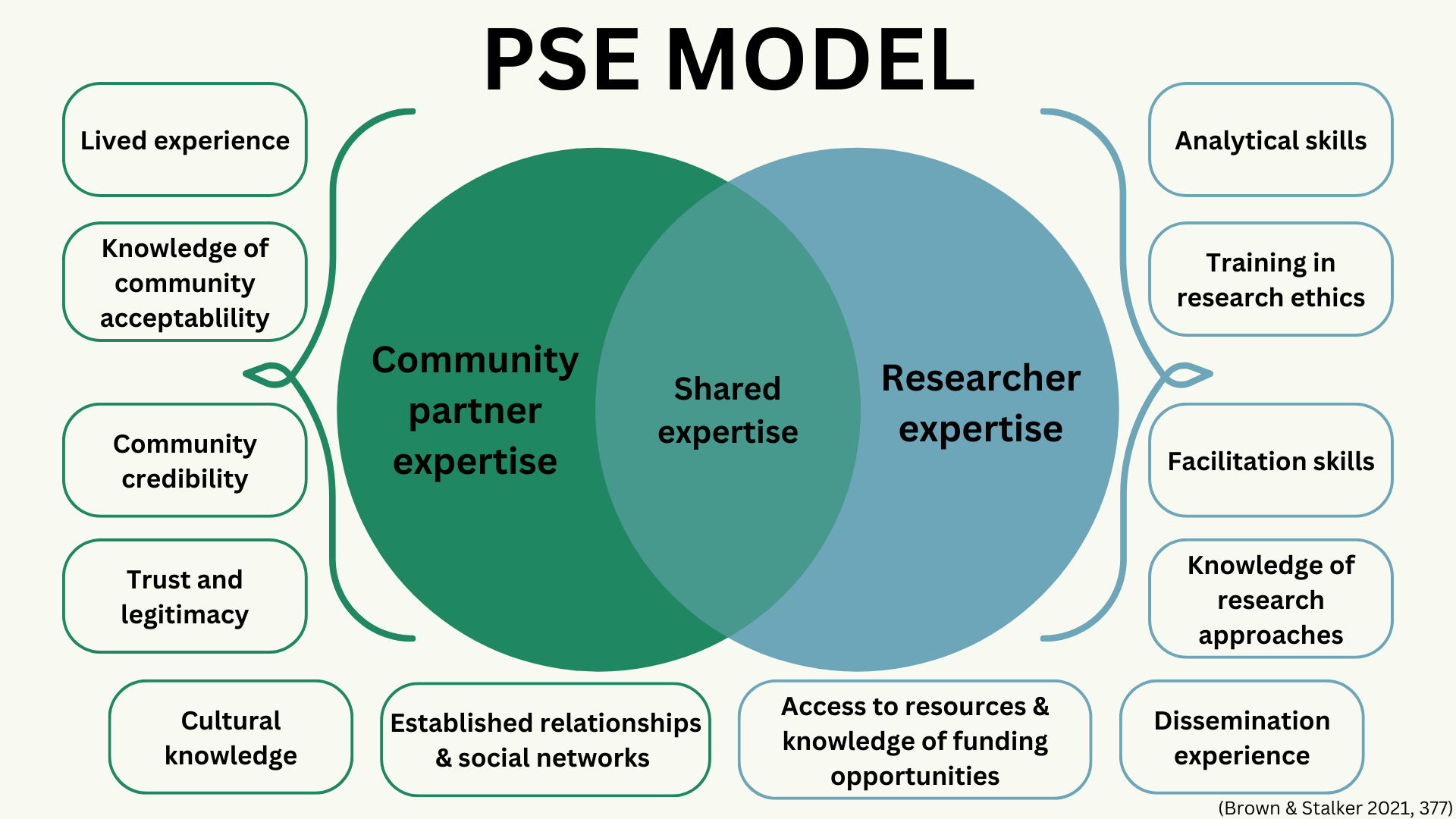

The principle of shared experience (PSE) model above illustrates the different expertise of the community partner and the researcher, and then in the middle. The shared expertise of the two.

The principle of shared expertise and the public health critical race praxis (PHCR) are two major principles that interact with CBPR.

The principle of shared expertise.

The principle of shared expertise puts forth the idea “that discussions in which researchers and community partners have equal space and power to share their perspectives and knowledge, and ultimately jointly make decisions, will result in a research design that optimizes both scientific rigor and community authenticity”(Brown et Stalker). In other words, the principle of shared expertise involves engaging in discussions where researchers and community partners have equal opportunities and authority to express their perspectives and knowledge, leading to collaborative decision-making. One of the challenges that comes with the CBPR research approach is the struggle to balance the wide array of different experiences and expertise that community partners and academic researchers bring to the table, which can lead to tension and disagreements. By employing the principle of shared experience, this challenge can be addressed “by [requiring] CBPR researchers not only to recognize but also to fully embrace the experiences, skills, and knowledge that community partners supply for the benefit of the project” (Brown et Stalker). This way, collaboration can develop so that the unique perspectives and skills of both partners are considered and effectively employed throughout the project.

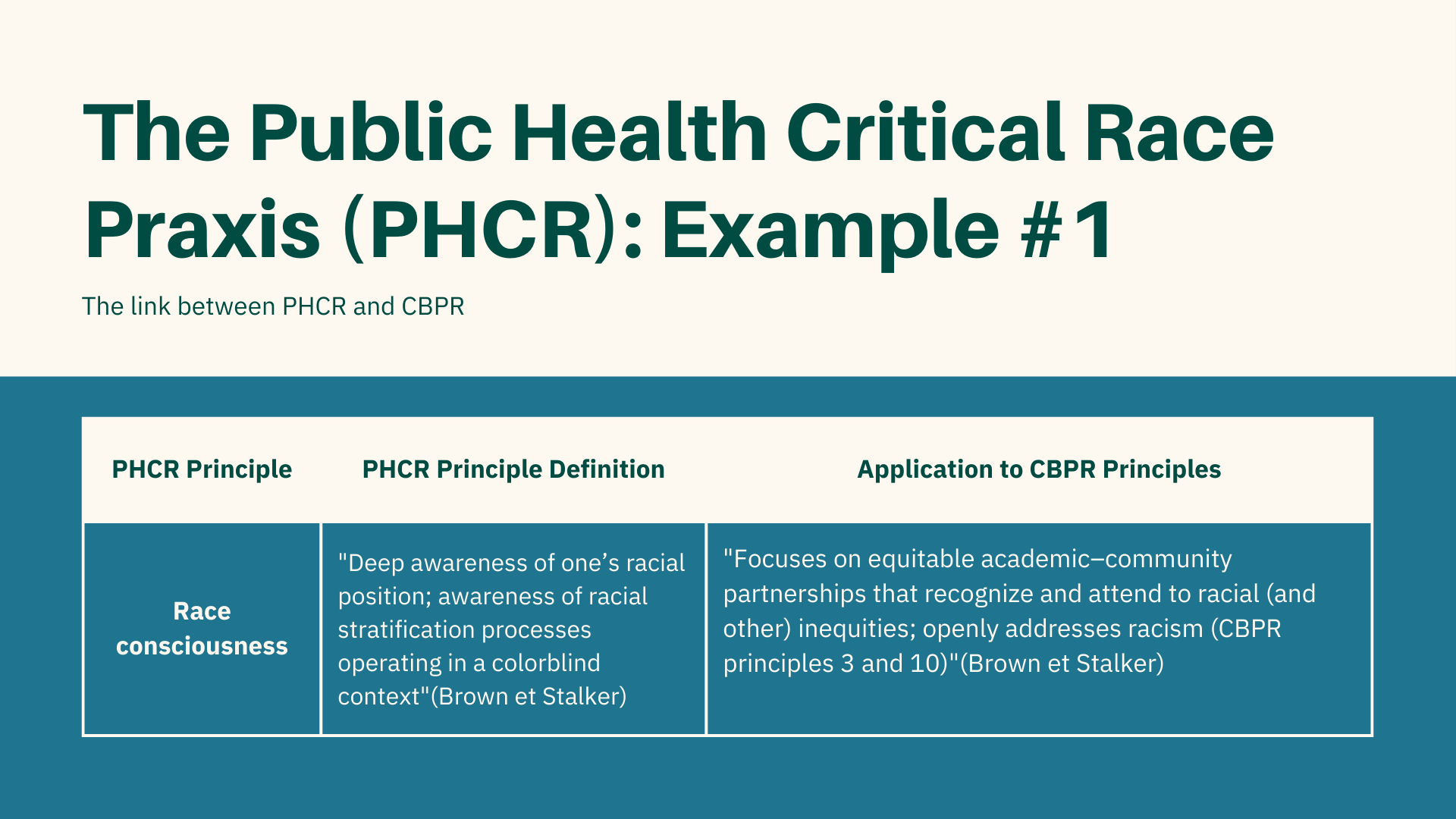

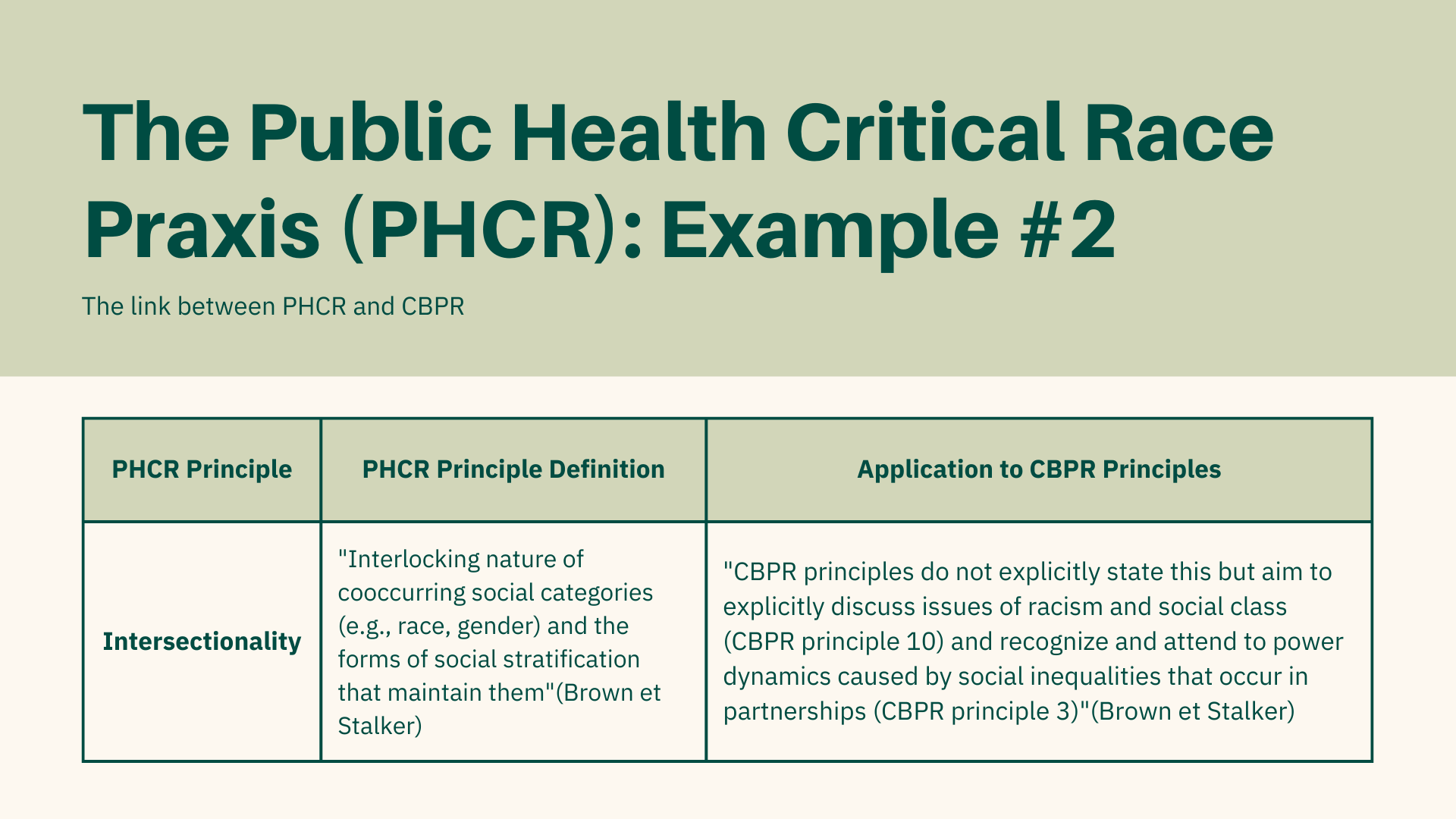

The public health critical race praxis.

When employing the CBPR research approach, it is crucial to recognize the pervasive influence of systemic white supremacy, as it creates significant obstacles in achieving inclusive and antiracist CBPR collaborations. White supremacy has “been created and constructed over centuries to value the lives, institutions, and knowledge of White people and devalue the human dignity and lives of Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Arab, Asian, and other marginalized groups” (Fleming, Paul J, et al). For instance, sickle cell disease, which predominantly affects black Americans, receives considerably less attention and support from the NIH and US philanthropic organizations compared to diseases that are more prevalent in the white population (Fleming, Paul J, et al). The public health critical race praxis (PHCR) is an antiracism framework for health research that aims to uncover and address the root causes of racial hierarchies by incorporating principles from critical race theory (CRT) into health research, with the aim of promoting antiracist approaches. PHCR principles thus align with CBPR’s focus on prioritizing the empowerment of marginalized communities and actively working to dismantle various forms of inequities (Fleming, Paul J, et al).

Funding for CBPR

Proper funding is essential for CBPR projects to promote community engagement and prevent unequal power dynamics between partnerships. With that being said, CBPR faces multiple challenges regarding funding.

Challenge 1:

Difficulty funders face in defining their role within CBPR partnerships leading to uncertainty regarding commitment to CBPR

With multiple partnerships engaged in CBPR projects, such as community-based organizations and academic researchers, funders may face challenges in determining their specific role within the partnership that may lead to uncertainty in starting or expanding commitment to CBPR projects (Minkler, M. et al.). The question of whether funders should be regarded as active partners in the CBPR project or should adopt a more passive approach, giving greater autonomy to the community and research partners, remains a topic of discussion. One proposed compromise suggests finding a middle ground. In this approach, funders allow space for autonomy within the CBPR project while actively participating as key players by providing assistance and support to other partnership members (Minkler, M. et al.). An example of this middle ground approach is observed through the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), a funder that provides “community-driven environmental justice grants” (Minkler, M. et al.). The role of NIEHS involves encouraging collaboration among partner representatives from the various environmental justice projects it supports. The partner representatives meet annually in order “to promote co-learning and provide direct technical assistance” (Minkler, M. et al.). NIEHS, however, remains “an ‘outsider’ in these meetings keeps it from impinging on the autonomy and self determination of its grantees”(Minkler, M. et al.). NIEHS thus demonstrates an approach for funders to define their role with CBPR partnerships that both supports and makes space for autonomy. Furthermore, essential to cement the funder’s commitment to CBPR is the establishment of a distinct role that provides support as well as allows for autonomy among other partnership members.

Challenge 2:

Lack of investment by funders in front-end processes leading to a lack of community building

As CBPR often focuses on lower-income communities of color, funding for front-end processes, particularly in community building, is essential. In the context of CBPR, front-end processes are defined as the initial activities and strategies that engage the community directly. Examples include health education and promotion, as well as school health programs. Front-end processes that engage in community building, specifically, are an important first step in CBPR projects in order to promote collaboration between community members and researchers, and encourage active-participation of community members in data collection and decision-making processes with the goal of ensuring that interventions effectively address the community’s specific needs. Thus, investing in front-end processes, particularly CBPR projects in these communities is important to create an environment that empowers the community to engage and collaborate, setting the stage for a sustainable and impactful CBPR project. For example, in Oakland, California, the city’s Enterprise Community Project involved various training that included teaching “20 community members to conduct, and help analyze data from, a massive door-to-door survey campaign” (Minkler, M. et al.). Many of the participants continued to stay involved in research and community work years after the start of the project demonstrating the impact front-end processes have in creating long lasting community partnerships and therefore, the importance in funding for these processes.

Challenge 3:

Funders’ limitation to provide adequate and flexible funding

Adequate compensation for all team members and flexible funding is important for the success of CBPR. As collaboration with community members is a key part of CBPR research, ensuring they are adequately compensated via stipends for their work is important. Adequate funding looks like paying participants a fair salary for their time or paying workers a livable wage if they are working full time. Additionally, it can take time to build relationships between community members and researchers, which is why flexible funding is essential so that the project has adequate front-end time to build these strong relationships before research begins. Flexible funding may look like reduced restrictions regarding funding that allows a more fluid timeline so that the CBPR team can adjust the project to the needs of the community without a time constraint that may rush the project and lead to unsuccessful results. Without the constraints of traditional funding that has strict guidelines, flexible funding is needed to allow the project to adapt to the community needs and priorities. Furthermore, by addressing these three challenges in regards to funding, funders can best support sustainable and effective CBPR projects.

Conclusion

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is a powerful and transformative approach to research that aims to address health disparities and promote health equity by fostering collaborative partnerships between scientific researchers and community members. By prioritizing equitable community involvement, CBPR seeks to build community capacity, design culturally tailored interventions, and achieve sustainable improvements in health behaviors and outcomes among health disparity populations. The CBPR process follows a fluid feedback loop model with seven core phases, emphasizing community engagement, data collection, and continuous evaluation. To maximize the impact and effectiveness of CBPR projects, it is crucial to embrace the principles of shared expertise and the public health critical race praxis (PHCR), which help address power imbalances and systemic inequities in research collaborations.